Because the Catholic kids had catechism on Thursday, we Protestants got Release Time, also on Thursday, so teachers had an easy day.

Because the Catholic kids had catechism on Thursday, we Protestants got Release Time, also on Thursday, so teachers had an easy day.

I was all about Bible stories, less so about the mile walk from Campbell School to First Presbyterian and 1.8 miles home, in the winter near dark if I couldn’t get a ride. At least most of my route followed Main Street in Metuchen, New Jersey—not exactly the wild side—and there was a dime store with candy but still . . .

The other down side of the long walk was way too much time to ponder My Problem.

Which was this. Sunday school teachers and the minister went on and on about The Word of God, never considering literal-minded eight year olds.

For example, they insisted that just as all parents love all their children equally (hah!), the Heavenly Father loves us all exactly the same. If so, I reasoned, wouldn’t He love all words equally since (presumably) He created them all? What made one word so darn special?

And if there is ONE word, THE word, why does the Bible have so many, including all those weird names, Abiasaph, Eidad and Medad, Hammedatha?

Really, one single word was enough to sustain Moses in the desert, Jesus being flogged and Apostle Paul wandering all over creation?

And if there is one word, why are we even talking? We should just be all the time going, “Word, Word,” he said. Then “Word, word,” she answered and everybody’s happy and blessed.

I considered options: Jesus, faith, salvation. Then what about the Old Testament? No Jesus there.

I didn’t consider asking the minister, an austere individual who generally avoided children, and finally accosted a Sunday School teacher. That is, I ambushed her in front of a toilet stall in the ladies room as she shifted from foot to foot in a way I’d never associated with adults, therefore not suspecting that her bladder issue might be more urgent than my theological query.

So I persisted. “What is the Word of God?”

“It’s what we believe. It’s what we talk about all the time.” Her voice rose. Had I not been listening? Was I hiding a comic book in my collected stories of Protestant missionaries and martyrs?

I fumbled. “I mean which one is the Word of God? There’s so many.” There, I’d got it out.

“The Word of God,” she began, reaching out her hand. To bless me? No, to shove me aside from the toilet, her Mecca. “The Word of God . . . is love.”

I might have gotten an “oh” in before she clicked the latch from inside her stall.

“OK?” came her disembodied voice.

“OK,” I said. It was a cold day, I remember, and The Answer didn’t warm me that much all the way home.

I must have been about eight when I read a passing reference to a boy who organized his mind every evening. Unbelievably, the writer barreled on without explaining how, but the project seemed so essential that I decided I must undertake it and for some reason assumed the project must be secret.

I must have been about eight when I read a passing reference to a boy who organized his mind every evening. Unbelievably, the writer barreled on without explaining how, but the project seemed so essential that I decided I must undertake it and for some reason assumed the project must be secret. I’m sure I remember this, that it wasn’t a dream. What’s remarkable is the quality of sensations that are not exactly thoughts, as if they came before words. I’m very small, being held between the knees of someone much larger, my arms perhaps draped over these knees. My feet aren’t free. They’re in a sack of some sort, like a sleep sack.

I’m sure I remember this, that it wasn’t a dream. What’s remarkable is the quality of sensations that are not exactly thoughts, as if they came before words. I’m very small, being held between the knees of someone much larger, my arms perhaps draped over these knees. My feet aren’t free. They’re in a sack of some sort, like a sleep sack.

Through the 90’s, I taught college English in Naples, Italy at a US navy base. It was a remarkable experience, a world away from the ivy-aesthetics of grad school. In a decade of relative prosperity, with a low probability of combat duty, many enlisted to stay alive and find peace. Fully a quarter of one class had lost a close family member to violence. “If I wasn’t here, I’d be dead or in prison,” I heard over and over.

Through the 90’s, I taught college English in Naples, Italy at a US navy base. It was a remarkable experience, a world away from the ivy-aesthetics of grad school. In a decade of relative prosperity, with a low probability of combat duty, many enlisted to stay alive and find peace. Fully a quarter of one class had lost a close family member to violence. “If I wasn’t here, I’d be dead or in prison,” I heard over and over. ’ll always remember a commercial for a brand of nothing-special wrapped candy from the years I lived in Italy. The production values were modest, as was the marketing claim, but the take-away has enduring resonance in real life (IRL).

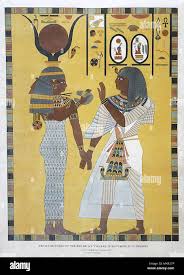

’ll always remember a commercial for a brand of nothing-special wrapped candy from the years I lived in Italy. The production values were modest, as was the marketing claim, but the take-away has enduring resonance in real life (IRL). In my tucked-in corner of New Jersey, Mr. Massuda the French teacher was an exotic. He was Egyptian, and while to some students’ surprise, he didn’t walk sidewise or write on papyrus, he came trailing a romantic past. Born into “une famille riche” which we escalated to villas, hanging gardens and lavish barges on the Nile, the family suffered a calamitous reversal and he was reduced to selling postcards of the pyramids (he said or we thought).

In my tucked-in corner of New Jersey, Mr. Massuda the French teacher was an exotic. He was Egyptian, and while to some students’ surprise, he didn’t walk sidewise or write on papyrus, he came trailing a romantic past. Born into “une famille riche” which we escalated to villas, hanging gardens and lavish barges on the Nile, the family suffered a calamitous reversal and he was reduced to selling postcards of the pyramids (he said or we thought). At age 9, I decided to be the first Protestant saint, which would catapult me into a new edition of A Child’s History of Heroes and Heroines. I knew this was a stretch. My Sunday school teachers had been quite clear that Protestantism doesn’t do saints.

At age 9, I decided to be the first Protestant saint, which would catapult me into a new edition of A Child’s History of Heroes and Heroines. I knew this was a stretch. My Sunday school teachers had been quite clear that Protestantism doesn’t do saints. “The mark of a good scientist is enjoying problems,” my father maintained, “seeking them out.” This problem passion helped him build a distinguished career in chemical research, developing some of the drugs he used himself for cancer and Parkinsons.

“The mark of a good scientist is enjoying problems,” my father maintained, “seeking them out.” This problem passion helped him build a distinguished career in chemical research, developing some of the drugs he used himself for cancer and Parkinsons. We are staying near Uvita, on the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. This morning I went to a little shop that has a couple samples of almost anything you could want. I noticed too late that the clerk was putting my groceries in a paper bag and held up my cloth one.

We are staying near Uvita, on the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. This morning I went to a little shop that has a couple samples of almost anything you could want. I noticed too late that the clerk was putting my groceries in a paper bag and held up my cloth one.